|

By: Vince Parisi, AmeriCorps State & National Member Chicago set a record high temperature on Monday June 17th, with a temperature 16 degrees above normal as record breaking heat has become increasingly common in the city. As the effects of climate change continue to be felt by Chicagoans and humans across the globe, summers can only be expected to get hotter.

Urban Heat Islands “occur when cities replace natural land cover with dense concentrations of pavement, buildings, and other surfaces that absorb and retain heat. This effect increases energy costs, air pollution levels, and heat-related illness and mortality” according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Chicago could see up to 30 more days per year with temperatures above 100 degrees with continued high greenhouse gas emissions. Heat Islands can disproportionately affect those living in historically low income neighborhoods, including most of the families that participate in our Chicago HOPES for kids after school programs. As part of our Chicago HOPES network it is important to understand the impacts of Urban Heat Islands and what can be done to mitigate their effect. Impacts of Urban Heat Islands Increased Energy Consumption: Urban areas are typically densely covered in non-permeable surfaces like roads, sidewalks, and buildings, with few trees and little vegetation. As temperatures increase, heat is absorbed and reflected by the non-natural surfaces resulting in surface temperatures that can be 15 to 20 degrees warmer than surrounding areas. These higher surface temperatures cause air conditioning units to work harder to cool buildings, and while doing so consume more energy resulting in increased greenhouse gas emissions. During peak energy demand, typically on summer afternoons, heat island effects increase the strain on the electrical grid and may cause municipalities to implement rolling blackouts in order to prevent power outages. Elevated Emissions of Greenhouse Gasses: To supply the power for increased demand on air conditioning units during heat island effects, companies typically rely on fossil fuels to supply the power needed. Heat island effects, themselves exacerbated by climate change and increased temperatures, in turn cause greater greenhouse gas emissions and further the effects of climate change. Additionally, greater greenhouse gas emissions can increase urban air pollution. In 2023, Chicago experienced the second highest level of air pollution among major US cities. Urban heat islands will continue to exacerbate the impact air pollution has on the health, educational, and economic outcomes of city residents and children in particular. Compromised Human Health: Heat-related mortalities are the leading cause of weather related deaths in the United States, despite being preventable. Urban heat island effects lead to an increase in heat-related deaths and heat-related illnesses like heat exhaustion, heat cramps, and non-fatal heat stroke. Heat islands disproportionally affect the health of older adults, young children, and low-income populations:

Heat Island Effect Mitigation Local governments and municipalities can employ several strategies to reduce the increased surface temperatures that result from urban heat islands in tandem with efforts to raise awareness of residents that may be impacted. The implementation of early warnings of extreme heat to residents and availability of cooling centers are one way a municipality can protect the safety of residents while heat island effects are being experienced. The primary methods to mitigate heat island effects in the long term are as follows: Increasing tree and vegetative cover: On average, urban forests have temperatures three degrees lower than surrounding areas, as trees and vegetation lower surface temperatures by providing shade. Through a process called transpiration, they absorb water through their roots and release the vapor through their leaves, further cooling surrounding areas. In addition, trees and vegetation can decrease pollution by lowering air conditioning costs, and store carbon dioxide from the air. They improve water quality by storing and filtering runoff and treeshade can slow the deterioration of pavement. Trees cover just 19% of the area of Chicago, while by comparison Atlanta boasts 47.9% coverage. According to a 2010 editorial Chicago has lost 10,000 more trees than it has planted each year on average. Installing green roofs and cool roofs: Green roofs, or rooftop gardens, provide shade, remove heat and lower temperatures of the surrounding air through the same processes as trees and vegetation. Green roofs can be 30-40 degrees cooler than traditional roofs and reduce city-wide temperatures by 5 degrees. Cool roofs are made of highly reflective materials that remain cooler than other materials in peak temperatures. While both are effective strategies for reducing heat island effects, green roofs also absorb stormwater and carbon dioxide from the air while connecting residents and wildlife to the built environment through green space. Installing cool and permeable pavements: While conventional pavements can absorb 80-95 percent of sunlight, cool pavements use additives to create a surface that reflects solar rays. Permeable pavements absorb less heat than traditional pavement by containing pores that allow water to drain and evaporate, retaining runoff and cooling the ground level surface temperature. In summary, as the effects of climate change continue to be witnessed, it is important for cities to acknowledge and prepare for increasing instances of extreme heat. Chicago lacks the tree canopy needed to sufficiently mitigate the strain on the electrical grid that will result from increased heat island effects. In addition, many of its most vulnerable residents are at risk of heat-related illness and death due to housing instability and a lack of access to air conditioning. If the city wants to ensure a sustainable and safe future for its residents, a concerted effort to plant more shade trees and surface vegetation should be made, with potential incentives for homeowners and businesses to install green roofs. References: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Reduce urban heat island effect. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved June 28, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/reduce-urban-heat-island-effect U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Learn about heat islands. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved June 28, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/learn-about-heat-islands U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Heat island impacts. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved June 28, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/heat-island-impacts Cool pavement. (2024, June 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cool_pavement Green, M. (2023, June 12). Chicago prepares for rising summer temperatures. Axios. https://www.axios.com/local/chicago/2023/06/12/chicago-summer-temperature Friends of the Chicago River. (n.d.). Restore Chicago’s tree canopy. Friends of the Chicago River. Retrieved June 28, 2024, from https://www.chicagoriver.org/blog/celebrate-margaret-frisbie-s-20th-year-at-friends/6/restore-chicago-s-tree-canopy Trees Atlanta. (n.d.). Urban tree canopy study. Trees Atlanta. Retrieved June 28, 2024, from https://www.treesatlanta.org/resources/urban-tree-canopy-study

0 Comments

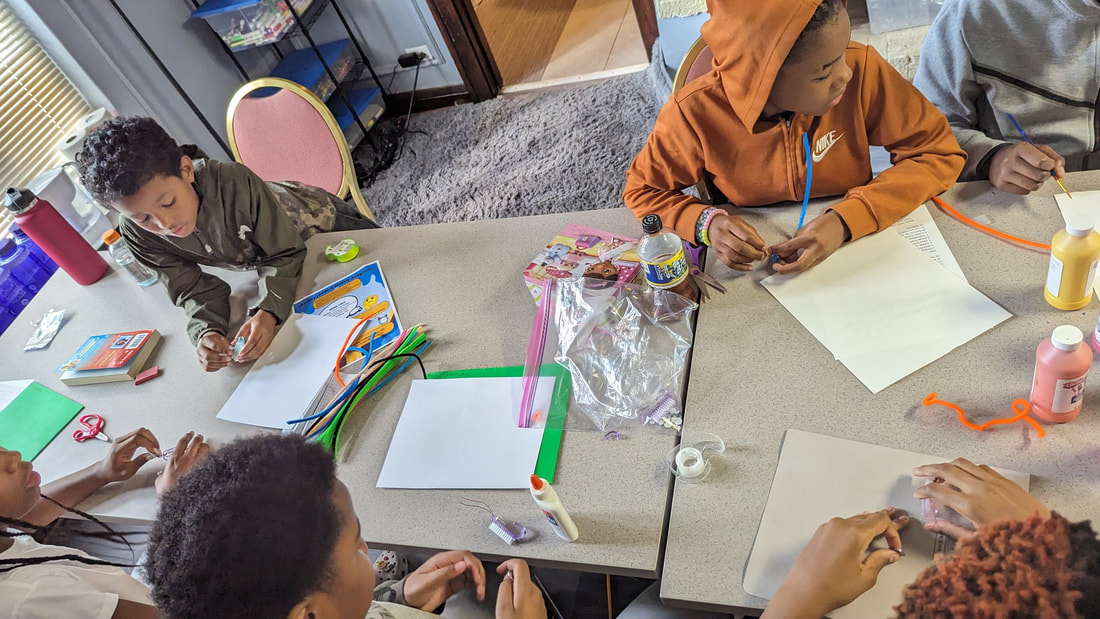

By: Tyler Hughes, AmeriCorps State & National Member In the realm of education, afterschool programs emerge as vibrant hubs where learning, enjoyment, and personal development intersect seamlessly. They transcend the conventional boundaries of classrooms, acknowledging their fundamental significance in shaping the paths of the upcoming generation.

Afterschool programs serve as indispensable extensions of the school day, furnishing a secure and organized setting for students. Customized to accommodate diverse requirements, they furnish academic reinforcement, skill enhancement, and enrichment pursuits. Significantly, they address academic and socio-emotional needs, particularly among economically challenged families, providing reassurance to working parents (Afterschool Alliance et al., 2020). These programs play a crucial role in tackling alarming statistics: Over 15 million students—approximately 3.7 million of whom are in middle school—are left unsupervised between 3 and 6 p.m., prime hours for juvenile delinquency and risky conduct (Afterschool Alliance et al., 2020). By offering a supportive environment during these times, afterschool programs steer students away from negative influences, while also acting as bridges between families and community resources. They often furnish essential snacks or meals, alleviating stress for working parents. Additionally, afterschool programs wield a profound influence on academic achievements, school attendance, and socio-emotional learning, especially benefiting underprivileged students by narrowing achievement disparities and enhancing college and career readiness skills among older adolescents (Vandell et al., 2007). Furthermore, the advantages of afterschool programs extend beyond academic accomplishments. Studies indicate they cultivate positive behaviors and aspirations for higher education, contributing to a culture of academic distinction (Smink & Expanded Learning & Afterschool Project, 2013). Moreover, they diminish tardiness, reduce dropout rates, and mitigate juvenile delinquency and substance abuse (Council for a Strong America, 2019). Afterschool programs can also promote community engagement and social cohesion by engaging the community in planning and activities, fostering collaborative projects, celebrating diversity, integrating service learning, hosting events, forming partnerships, emphasizing community-based learning, implementing peer leadership programs, encouraging parent involvement, and maintaining open communication channels. These endeavors aid in forging stronger bonds between students, families, and the wider community, fostering a sense of belonging and civic duty. Through community-oriented objectives and initiatives, youth discover a sense of empowerment and healing as they recognize their capacity to effect positive change (BUILD, Inc., 2023). Despite their myriad advantages, financial limitations often hinder access to afterschool programs, disproportionately affecting low-income households (Afterschool Alliance et al., 2020). One recommended approach to support and expand afterschool programming is through Policy Advocacy Coalitions. These coalitions, comprised of educators, parents, and advocates, collaborate to advocate for increased funding and support for afterschool programs at the state level (California Afterschool Advocacy Alliance (CA3), n.d.). Through grassroots mobilization, public awareness campaigns, and legislative lobbying endeavors, the coalition endeavors to secure additional resources and policy alterations that broaden access to quality afterschool programming statewide. In conclusion, afterschool programs serve as catalysts for positive transformation, empowering youth, aiding families, and fortifying communities. Recognizing the pivotal role these programs fulfill is essential for nurturing the leaders of tomorrow and constructing a brighter future for all. By investing in afterschool programs, society invests in the potential of its youth, ensuring they are equipped with the skills, support, and opportunities requisite to thrive in an ever-evolving world. References: Afterschool Alliance, Edge Research, Burness, Anthony, K., Blyth, D., Chung, A.-M., Colman, A., Gwaltney, R., Hall, B., Sari, P., Lake, S., Little, P., Moroney, D., Roehlkepartain, E., Sneider, C., Warner, G., & Wills-Hale, L. (2020). America after 3PM Demand grows, opportunity shrinks. In America After 3PM [Report]. https://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2020/AA3PM-National-Report.pdf California Afterschool Advocacy Alliance (CA3). (n.d.). About Save After School — California Afterschool Advocacy Alliance (CA3). CA3. https://ca3advocacy.com/about Council for a Strong America. (2019). From risk to opportunity: Afterschool programs keep kids safe. https://www.strongnation.org/articles/930-from-risk-to-opportunity-afterschool-programs-keep-kids-safe Smink, J. & Expanded Learning & Afterschool Project. (2013). A proven solution for dropout prevention: expanded learning opportunities. In Expanding Minds and Opportunities: Leveraging the Power of Afterschool and Summer Learning for Student Success. https://www.expandinglearning.org/expandingminds/article/proven-solution-dropout-prevention-expanded-learning-opportunities Vandell, D. L., Reisner, E. R., & Pierce, K. M. (2007). Outcomes Linked to High-Quality Afterschool Programs: Longitudinal findings from the Study of Promising Afterschool Programs. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED499113.pdf By Faith Benson, AmeriCorps State & National Member A child’s school experiences play a huge role in healthy child development. Since most children spend a large portion of their childhood attending school, maintaining a stable and consistent school environment is vital to a child’s functioning both within that space and outside of it. Research has shown that children thrive on predictable routines (Hemmeter, 2006). Alternatively, children who change schools multiple times throughout their academic years are at developmental risk, emotionally, socially, and academically. In a national survey of K-8 students from 1998 to 2007, thirteen percent of all students changed schools four or more times within those eight years. (Government Accountability Office, 2010). Although there are many different reasons a child may be changing schools frequently, experiencing homelessness is the highest predictor. According to district data from Chicago Public Schools in the 2023-2024 school year, the number of students in temporary living situations (STLS) was 17,700 kids. That total is up 64 percent when compared to 2021-2022 when there were 10,836 STLS students identified (Matt Masterson, 2024). Parents, school staff, and social service personnel should be aware of the developmental risks moving frequently is having on children experiencing homelessness.

By definition, child development is the entirety of the time a child grows from full dependence on their caretaker into independent adulthood. This time period can look different for different individuals but it is usually from birth until a person is 18 or 21 years old. Child development includes all the changes a child goes through biologically, socially, emotionally, and in this case, academically. When a child’s development is said to be at risk, their socioemotional functioning is being threatened by some outside factors. Child development can be negatively impacted by many different types of adversities. Changing schools frequently throughout the early academic years is just one variable that can lead to a plethora of developmental delays. The first category of developmental risk moving homes and schools can have on a child pertains to emotional well-being. Children who are still developing experience many complex emotions that they have not dealt with before, such as their sense of identity, their self-esteem, and the ability to self-regulate their emotions. Oftentimes, beginning new grades, changing classrooms, or joining new extracurricular activities can be stress and anxiety-inducing for a child. On the flip side, remaining in the same school for a couple of years can help children develop familiarity with teachers and peers outside their classrooms. This reinforces a sense of belonging and overall emotional stability within the school environment (Entwisle and Alexander, 1998). Alternatively, children who have a history of frequent school changes may lead to that child to emotionally withdraw. In other words, the child could refrain from emotional investment in his peers and teachers because they feel as though another move is inevitable (Grigg J, 2012). Another way frequently moving negatively manifests itself in the classroom is a fear of trying new things, and anxiety surrounding transitions from one activity to the next. The second category of developmental risk changing schools can have on a child is with regard to their social interactions. For a developing child, the social aspect of school is arguably just as important as the academics. From a very young age, children are learning how to interact socially with peers and adults. They are learning who they are and what role they want to play within different social groups and environments. Thus, a large part of school is learning how to form social connections and bonds with one's classmates as well as their authority figures. For better or worse, many schools have a sort of established social system or hierarchy. Always being the new kid can make it close to impossible for that child to engage in social settings. Research has found that adolescents who move schools frequently tend to be more socially isolated and less involved in extracurricular activities than non-mobile adolescents (Pribesh, 1999). Children experiencing homelessness can also feel isolated when they try to engage with peers who have different living experiences and socioeconomic statuses than them. The third and final impact changing schools has on adolescents is lower academic performance. When children change schools they are at risk of missing out on materials, their grades dropping, and even having to repeat grades. Whether the child changes schools in the middle of the academic year or at the beginning of a new grade, curriculum, expectations, and pace vary between schools. Thus, any change can be taxing on a child’s academic performance. According to data from the University of Michigan's Panel Study of Income Dynamicound, “the number of moves the children made at ages 4-7, as well as at ages 12-15, had a significant and negative impact on whether the children had graduated from high school by the time they were 19-24 years old” (Moving On, 1998). As a society, we must understand and advocate for healthy child development. When a child frequently moves schools their emotional, social, and academic development are at risk. Early intervention in these scenarios may diminish long-term risk. Granted, moving is a part of life and unavoidable at times, but not in all cases. Spreading awareness about the risks that frequent moves have on a child can help parents, schools, and social service agencies better support children and families experiencing homelessness. The McKinney-Vento Act is one policy that advocates for children experiencing housing insecurity to not only remain in one school regardless of their living location but also attempt to alleviate some of the logistical strains that come with changing school districts. This Act was established to protect the educational rights of children experiencing homelessness. There are multiple facets of the McKinney-Vento Act as it pertains to what schools are required to provide pro-bono to youth experiencing housing insecurity. The first is documentation. According to McKinney-Vento, schools cannot delay a child’s enrollment due to missing documentation such as medical records, birth certificates, proof of residence, and proof of guardianship. This Act also protects undocumented students as it is illegal for schools to inquire about immigration status. Additionally, unaccompanied youth can enroll without a parent or guardian. The next section of this Act is additional school fees. According to McKinney-Vento, schools must waive all additional school fees for children experiencing homelessness. These fees include field trips, uniforms, sports equipment, school supplies, graduation, school dances or other events, and school lunches. In addition to this, school-aged children experiencing homelessness are always eligible for school services such as tutoring, counseling, before and after-school programs, and health services. The third and final section of this assistance act pertains to transportation. Under McKinney-Vento, Chicago public schools must provide bus transportation to and from the kid’s school or origin. A child’s school of origin is simply the school that they attended when they were permanently housed, or the school they began the school year off at. Additionally, children who become permanently housed during the school year are still eligible for transportation to their origin school until the end of the year (Chicago HOPES, 2022). During Chicago HOPES parent enrichment programs, the agency informs parents about the rights their children have through the McKinney-Vento Act. Many parents may be unaware of these rights, and when parents don’t actively pressure school faculty to adhere to the McKinney-Vento policies, schools may not always abide by these criteria. HOPES is an agency committed to advocating on behalf of underresourced communities as well as empowering those communities to stand up and advocate on their own behalf. The transportation section of McKinney-Vento also impacts HOPES in the sense that children involved in HOPES after-school programs are from many different schools. Sometimes kids have to come to the program late because their commute to school is much further than the local school district would be. In the same way, kids have different types of homework and teacher expectations because everyone staying at one of HOPES homeless shelter sites are not from the same school. This is one of the reasons Chicago HOPES creates individual tutoring plans for each child enrolled in their programs. Recognizing that the children in the programs have a diverse array of experiences, abilities, and academic skills, is an important step to meeting the kids where they are at. Individualized curriculum is not always an easy task, but it’s one of the aspects that makes HOPES programs so effective in improving children’s academic performance. References: Chicago HOPES for Kids. (2022). Resources. https://www.chicagohopesforkids.org/resources.html Entwisle DR, and Alexander KL 1998. “Facilitating the Transition to First Grade: The Nature of Transition and Research on Factors Affecting It.” The Elementary School Journal 98 (4): 351–364. Government Accountability Office 2010. K-12 Education: Many Challenges Arise in Educating Students Who Change Schools Frequently. No. GAO-11–40. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office. Grigg J 2012. “School Enrollment Changes and Student Achievement Growth: A Case Study in Educational Disruption and Continuity.” Sociology of Education 85 (4): 388–404. doi: 10.1177/0038040712441374. Hemmeter, Mary Louise; Michaelene Ostrosky, and Lise Fox. "Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning: A Conceptual Model for Intervention."School Psychology Review 35(4) (2006): 583–601. Matt Masterson, WTTW News. “How Chicago Public Schools Tracks and Supports Its Unhoused Student Population: FIRSTHAND: Homeless.” WTTW Chicago, 19 Feb. 2024, interactive.wttw.com/firsthand/homeless/how-chicago-public-schools-tracks-and-support s-its-unhoused-student-population#:~:text=According%20to%20district%20data%2C%2 0the,were%2010%2C836%20STLS%20students%20identified. "Moving On": Residential Mobility and Children's School Lives Author(s): C. Jack Tucker, Jonathan Marx, and Larry Long Source: Sociology of Education, Vol. 71, No. 2 (Apr., 1998), pp. 111-129 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2673244 Pribesh S, Downey DB. Why are residential and school moves associated with poor school performance? Demography. 1999; 36(4):521–534. By: Vince Parisi, AmeriCorps State & National Member Gentrification is the process of neighborhood change that results from an influx of higher income residents. It is most often used as a pejorative to describe the displacement that can result when the original neighborhood residents can no longer afford to pay rent or property taxes on their accommodations. Displacement can occur directly through lease-non renewals, evictions, or physical conditions that make housing uninhabitable, indirectly due to rent increases, or culturally when services and shops have shifted to cater to a changed population. When higher income residents move to the city from surrounding areas, they bring valuable tax dollars that can help fund improvements, but in doing so may disrupt the lifestyle and livelihood of long-term neighborhood residents. While gentrification is a byproduct of an American capitalist economy, policy tools and strategies exist that help prevent unjust displacement and help keep urban neighborhoods places where people of all income levels and cultural backgrounds can share.

The relationship between American cities and their residents has been storied and complex. In the period following World War II, those who could afford it, often white middle class Americans, left the crowded cities for a new vision of the American Dream; a single family home, a yard, and a personal vehicle. This trend increased throughout the end of the 1900’s and was furthered by the dot com boom of the early 2000’s. However, today, as the millennial generation has begun to buy homes, a reversal of these earlier trends is becoming visible - young people want to live in cities. Citing a desire to escape from car-dependency and have access to walkable neighborhoods, public transportation, and live with a decreased carbon footprint, demand for urban housing and rentals has increased. While Chicago is still relatively affordable compared to other major American cities, this may make it a target for increased demand and gentrification in the near future. Pilsen is one area of the city that has experienced significant gentrification over the last three decades. The neighborhood was originally made up of Polish and Czech immigrants, but began receiving an influx of Mexican residents after World War II. Then, after the displacement of many Latino Chicagoans from the construction of UIC in the 1960’s, the area became one of Chicago’s first Latino-majority communities. Recently, from 2006 to 2020, the median household income in the Pilsen neighborhood has increased by almost 150%, primarily from the influx of white millennial residents. In response to the willingness of new residents to pay more for housing, and increased neighborhood rents, the City of Chicago has employed several strategies to preserve housing affordability in Pilsen, like the 2021 Anti-Deconversion ordinance that prohibits the conversion of multi unit buildings into single family homes. The following are additional policy tools that can be employed by city governments to preserve housing affordability and prevent displacement: Longtime Owner Occupants Program - This is a real estate tax relief program for homeowners, or occupants of a residency for the past 10 years. If the tax assessment has increased by more than 50% in the past year, this program caps the amount of an increase to 50%. To qualify for this program you must be current on property taxes or on an installment plan, and have an income below the limit for your family size. Single Room Occupancy Preservation/Protection - Single room occupancies or residential hotels typically house one or two people in a single room with a shared kitchen and bathroom. Single room occupancies can provide a safe, and accessible shelter for low income individuals, or people in transition. Unfortunately, many communities have adverse reactions to the creation or preservation of single room occupancies, and as a result they can be far from the central city and disconnected from public transportation. Land Value Capture - When the public sector makes an investment in infrastructure or land use, the private individuals who own the land surrounding the location of the change make a much greater profit than the initial cost to build the infrastructure or make a land use change. In Chicago, examples are The 606 or the redevelopment of the Fulton Market area. Both investments created huge increases in the value of land surrounding these areas, and likely priced out many residents who lived in the area before the change. By using land value capture, the public sector can recoup a percentage of the increase in land value and reinvest it back into the public. This could mean more bike lanes in disadvantaged areas, or the conversion of an office building into affordable housing. Inclusionary Zoning - When an area begins to gentrify, developers soon begin to join in on the action. This often results in high rise apartment complexes intermixed with existing historic buildings. This can mean demolition, or landowners allowing their building to deteriorate into unlivable conditions so tenants are forced to move out, allowing them to sell their land to a developer for a profit. Inclusionary zoning forces new developments to dedicate a portion of their units to designated affordable housing. This allows for new development, but can provide ways for the original residents of the community to remain and reap the rewards the private sector has brought to a gentrified area. Gentrification that results in displacement is an unfortunate consequence of urban demand. Our overarching economic system causes the real estate market to function as an investment good, and when there is a scarcity of housing, land owners can make money on their investment. If the city wants to ensure that it will remain an accessible and inclusive place for the years to come, residents should become aware of strategies to mitigate the displacement that results from gentrification, and become involved with politics at their own local level, working to be educated about future changes within the city and using their collective voice to preserve housing affordability and access. References: Lang, R. E., & Sohmer, R. R. (n.d.). Legacy of the Housing Act of 1949. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10511482.2000.9521369 Florida, R. (2023, April 14). Three years into the pandemic, the “Urban Exodus” was overblown. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-04-14/three-years-into-the-pandemic-the-urban-exodus-was-overblown Impact of gentrification | mapping global chicago. (n.d.). https://mappingglobalchicago.rcc.uchicago.edu/2023-elpaseo/gentrification/ Apply for the longtime owner Occupants Program (LOOP): Services. City of Philadelphia. (n.d.). https://www.phila.gov/services/payments-assistance-taxes/payment-plans-and-assistance-programs/income-based-programs-for-residents/apply-for-the-longtime-owner-occupants-program-loop/ The state of anti-displacement policies in LA County July 2018. (n.d.-b). https://knowledge.luskin.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/The-State-of-Antidisplacement-Polices-in-LA-County_071118.pdf Alliance, L. (2022, May 24). Land value capture, explained. Land Value Capture Explained. https://decentralization.net/2022/05/land-value-capture-explained/ Lashawn Gordon, AmeriCorps Volunteer In the heart of the South Side of Chicago lies the Englewood neighborhood Despite ongoing challenges such as poverty, unemployment and a lack of investment in the neighborhood throughout the neighborhood, the community stands strong. Currently, a movement is underway to change the lives of the residents and bring hope to the community. The movement’s goal is to make a positive change in the lives of children and families by shedding light on unrealized potential residing in Englewood along with providing resources such as educational support and assistance wWith a focus on empowering and equipping students with the tools they need to succeed in school and beyond, educational programs can become a beacon of hope for the community.

Education has always been a powerful tool for change and empowerment. In Englewood, it is no different; teaching children important academic skills and maintaining a sense of hope and possibility for a brighter future is significant. Dating back to the '60s, the systemic challenges facing the community have had an impacting struggle on Englewood's educational environment. The youth's development is hampered by a lack of extracurricular activities, crammed classrooms, and limited resources. However, behind these issues is courage, determination, and potential that, given the necessary assistance, may change the course of their young lives. According to the South Chicago Black Mothers’ Resiliency Project, “… despite living in high-violence neighborhoods, [parents] show resiliency and commitment to well-being through fostering safe and enriched childhood experiences for their children” (Imarenezor, O., 2017). This statement shows that programs for education designed specifically to meet the needs of Englewood children interest those within the community and. By tackling the obstacles head-on, these programs can provide a glimmer of hope, giving young people a way out of hardship. Providing access to high-quality education equips young brains with the information and vital life skills they need to overcome obstacles and create better futures. The achievement gap caused by issues that plague communities like Englewood can be mitigated by mentoring programs and tutoring services, which provide individualized direction and assistance to make sure that no talent is overlooked. In addition, educational programs in under-resourced communities provide secure learning environments for enrichment. For example, similar to our programs here at HOPES that serves in the Englewood community,, there are other community programs in place with components of tutoring, mentoring, and enrichment such as LevelUp and R.A.G.E. Furthermore, they provide financial assistance opportunities to young adults, teens, and children that may relieve financial burdens and give them the support they need to thrive academically. Beyond supplemental after-school support, there are educational institutions providing such services directly on their campuses. Urban Prep Charter Academy for Young Men at Englewood provides a positive school culture and rigorous college prep program. As a result, 100% of seniors have been accepted to 4-year colleges and universities. This success has also been driven by a community that values college education and believes in its students' ability to achieve, despite limited resources and limited control over enrollment (King T., 2011). It is important for students, children, and members of the community to have a safe space and that mentioned sense of belonging. It helps remind the youth that their dreams are within reach and that, despite the challenges, they are not alone on their journey. Educational programs are more than an investment in individuals; it's an investment in the community's collective future. By nurturing a diverse range of talents, these initiatives pave the way for innovation and economic growth within the community. This not only benefits individuals but contributes to the overall revitalization of Englewood. By acknowledging struggles, recognizing the immense potential, and fostering hope through tailored educational programs, we can empower youth to break free from the cycle of adversity and build a foundation for lasting success. Together, everyone can create a culture of support and encouragement within our community, where everyone's potential is recognized and nurtured. By investing in the education and future of our young people, we can empower them to overcome any obstacles and reach for their dreams. If you're eager to get involved, there are numerous ways to make a difference. Whether it's volunteering your time, participating in fundraising events, or spreading awareness about the work being done in Englewood, every action counts. Resources: LevelUp R.A.G.E Works Cited Imarenezor, O. (2017). Chicago Black Mother’s Project on Violence, Depression, Resilience, and Sociogenomics. Undergraduate Research Journal, 2. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Chicago-Black-Mother%E2%80%99sProject-on-Violence%2C-and-Imarenezor/7949d966488bd0c085de233eb13f9d627521bef3 King, T. (2011). Commentary: Swords, Shields, and the Fight for Our Children: Lessons from Urban Prep. Journal of Negro Education, 80, 191 - 192. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Commentary%3A-Swords%2C-Shields%2C-and-the-Fight-for-Our-King/cadac93096f76efb2649fe042004f6a5d8ec32a7 (1963). From the Publishers. The Elementary School Journal, 63, 462 - 464. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/460083 The Effects of Restorative Justice Practices on Black and Brown students with Disabilities9/28/2023 Jocelyn Tenorio, HOPES Development Manager Across multiple sources, the philosophy of Restorative Justice (RJ) has a common theme of humanizing students, rather than punishing them if they do something deemed as wrong. Rather than using punitive measures, such as detention, that work to physically exclude students, Restorative Justice practices seek to engage students and understand the root of their behavior. When engaging with historically marginalized Black and Brown students, educators should embed Critical Race Theory (CRT) alongside Restorative Justice practices when approaching students so as to not retraumatize them. Scholars also highlighted that though these practices are often a response to specific incidents, educators must instill Restorative Justice into the school’s culture using a whole-school approach. Though Restorative Justice practices have proven to be successful, one theme that has been widely neglected in these conversations is disability justice. Additionally, one must ask the question— what happens when the teacher is the offender? How does disability intersect with race, and how can Restorative Justice serve to mitigate potential harm? Whole school models have the potential to come to even greater fruition through policies.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) Brown (2021) argues that when educators use Restorative Justice practices, they need to engage with Critical Race Theory (CRT) and understand that Black and Brown individuals are largely suppressed in our society. Marginalized students already endure trauma and violence in their lives on a day-to-day basis, that be in the form of gang violence or microaggressions, therefore these practices must be trauma-informed so as to not retraumatize them. Comparably, Gwathney (2021) suggested a similar approach that applied Critical Race Theory (CRT) alongside ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences). A high ACE score (the more trauma experienced) indicates a higher risk for negative consequences, including low self-esteem and incarceration. In a case study done by Gwathney, they focused on following the journey of a Black, low-income student and found that his ACE score was an 8 out of 10 (Gwathney, 2021, pg. 351). Though assessments like these are helpful in teaching us how to approach trauma, we need to attribute the root of that trauma to certain systemic factors like racism. One way that Sandwick and colleagues (2019) suggest educators incorporate Critical Race Theory into Restorative Justice practices is through anti-racist, anti-bias, and culturally relevant pedagogy (Sandwick et al, 2019, pg. 25). However, Restorative Justice runs the danger of being used as just another disciplinary practice towards Black and Brown students. At the root of it, Restorative Justice originates from indigenous cultures, directly countering the white supremacist idea of punishment, and should be used to combat those ideas. Restorative Justice Practices Work In a case study by Brown, they focused on the effects of disciplinary measures in two middle schools on students. Davis Middle School in Oakland is a racially diverse school with students with disabilities, which had Restorative Justice practices in place, and Southern Middle School in Florida stuck to traditional punitive measures, was predominantly Black, and 19% of their students were diagnosed with a learning disability. Southern Middle School’s “In-School-Suspension (ISS) rate was 32%, while the Out-Of-School Suspension (OSS) rate was 47%.” Meanwhile, Davis Middle School had one of the lowest suspensions rates in the entire district (Brown, 2021, pg. 11). Looking at the qualitative data, Davis Middle School students, particularly the ones that were Peer Mediators, were cited by teachers to be more empathetic and confident. Though coming into less contact with the punitive school system is a sign that Restorative Justice practices work, and is a sign that students are not being retraumatized, this study did not have any particular data on the way that these practices impact Black and Brown/and or students with disabilities. Disability Justice and Educator Responsibility Ramirez-Stapleton and Duarte (2021) urge educators to use a disabilities framework when practicing Restorative Justice. According to their study, people with disabilities are the “largest minority group, with approximately one fifth of the US population experiencing disability at some point in their lives. The majority of those disabilities, approximately 74% will not be visible (e.g. learning disabilities, chronic pain, or mental health)” (Ramirez-Stapleton and Duarte, 2021, pg. 12). Duarte (a white Jewish woman) was Ramirez-Stapleton’s (a Black and queer woman) student during her undergraduate year for a deaf course, and Duarte had previously emailed Ramirez-Stapleton regarding accommodations that would be needed. Duarte was Deaf+ so she needed to have handouts in a larger font, however, her professor failed to do this on several occasions. There was an instance where Duarte had become very frustrated and left the class because again, she was not provided with the proper font size. While for Duarte this was an escape from a traumatic experience, Ramirez-Stapleton questioned if it was because she was a professor that was Black and queer. As the principles of Restorative Justice seek to include rather than to exclude students, disability framework which Ramirez-Stapleton and Duarte refer to as “‘understanding that all bodies are unique and essential, [and] that all bodies have strengths and needs that must be met” (para 13.), which includes not only students with disabilities and DDBDDHH [Deaf, DeafBlind, DeafDisabled, Hard of Hearing] students, but also students of color, undocumented students, queer students, students are parents, older students, and many others.’” (Ramirez-Stapleton and Duarte, 2021, pg. 12). Just as Ramirez-Stapleton was in the wrong, there should have been a dialogue built on these foundations of Restorative Justice and the disability justice framework so as to validate the feelings of her student at that moment, but to validate her humanity. Though this is only one example of the way that students with disabilities endure trauma, there are even more discrepancies when intersecting race and disability. According to a report done by the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO): K-12 Education Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities, “Black students with disabilities and boys with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined across all six actions. For example, Black students with disabilities represented about 19 percent of all K-12 students with disabilities and accounted for nearly 36 percent of students with disabilities suspended from school (about 17 percentage points above their representation among students with disabilities)” (GAO, 2018). The more historically marginalized students with disabilities are filtered out from our education system by such measures, the more they are likely to come into contact with our prison system. To mitigate this, Restorative Justice practices should not center their disability as an issue, rather it should work towards creating an individualized plan to accommodate them. It would not only serve to buffer that potential for future incarceration, but these students would have access to the education they deserve, free of trauma. School-Wide Restorative Justice While there are scholars who believe that particular individuals should lead Restorative Justice efforts, as is the case with Gwathney advocating for more social workers (Gwathney, 2021, pg. 353), other scholars advocate for it to be a school-wide effort involving all educators. Sandwick and colleagues point out that Restorative Justice should aim to change the culture among the entire school, which means teachers and administrators using skills such as mindful listening amongst themselves (e.g. staff meetings). They would not only use Restorative Justice practices in times of conflict amongst their students, but model how Restorative Justice philosophies serve to foster healthy relationships. An example of a school-wide approach to Restorative Justice could have been Ramirez-Stapleton listening to Duarte’s individualized needs, apologizing, and doing better to validate the humanity and needs of all of her future students. Brown urges educators to use this model across all environments, which can include an everyday classroom setting, field trips, parent events, etc. That said, it should operate from a Critical Race Theory (CRT) and disability framework. Conclusion Current literature supports the notion that Restorative Justice practices and a school-wide approach are one way to advocate for Black and Brown students, however, more of this research should focus on the intersection between race and disability. It is crucial to include the voices of Black and Brown students with disabilities. The systems in place disregard the mental health and disabilities of Black and Brown individuals, deeming it as bad behavior, which results in punishment instead of care. In what ways can schools be resources for these communities to have these conversations? How can we work towards inclusive policies that incorporate Restorative Justice outside of schools, such as in our prison system? Sources: Brown, Martha A. 2021. "We Cannot Return to “Normal”: A Post-COVID Call for a Systems Approach to Implementing Restorative Justice in Education (RJE)" Laws 10, no. 3: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws10030068 Ramirez-Stapleton, L. D., & Duarte, D. L. (2021). When you think you know: Restorative justice between a hearing faculty member and a Deaf+ student. New Directions for Student Services, 2021, 11– 26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20374 Gwathney, A.N. Offsetting Racial Divides: Adolescent African American Males & Restorative Justice Practices. Clin Soc Work J (2021). https://doi-org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/10.1007/s10615-021-00794-z Ramirez-Stapleton, L. D., & Duarte, D. L. (2021). When you think you know: Restorative justice between a hearing faculty member and a Deaf+ student. New Directions for Student Services, 2021, 11– 26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20374 Sandwick, Talia, Josephine Wonsun Hahn, and Lama Hassoun Ayoub. 2019. “Fostering Community, Sharing Power: Lessons for Building Restorative Justice School Cultures”. Education Policy Analysis Archives 27 (November):145. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.4296. Stephanie Salgado, HOPES Site Coordinator Time and time again, migrants and asylum seekers are marginalized as their humanity is ignored and their stories go untold or are blatantly overshadowed by persistent negative stereotypes. Their journeys, which often start with hope for a better future, a seemingly simple dream, is a dangerous and deadly reality. In addition to risking falling prey to kidnapping and exploitation, among other horrible fates, while they await their claim, asylum seekers are in a legal and social limbo as their lives are essentially put on hold as they operate under the threat of deportation. On top of the psychological stress and financial burdens, migrants and asylum seekers are met daily with racism, xenophobia, and discrimination. While not everyone shares these experiences, it is a reality for many who are hoping for a better life as they make the life-altering decision to resettle in a different country.

For decades, an integral part of United States immigration law is the right to asylum. At the same time, it has been a touchstone of the U.S. political debate for decades as sizeable ideological differences in immigration goals collide. More recently, the city of Chicago has seen a surplus of migrants, mainly from South and Central America which has been met with mixed reactions by media and communities. The first bus with migrants, sent from Texas under Republican Texas Governor Greg Abbott, arrived on August 31st of 2022. Since then, as of August 2023, over 12,000 migrants have arrived in Chicago (Hernandez, 2023). The city’s government officials and local organizations have been scrambling to supply these individuals and families with necessities and place them in temporary shelters. However, it quickly became increasingly clear that the city is not able to provide the necessary support for these new arrivals as migrants, including pregnant women and children, are being forced to sleep at police stations and public parks as they await space in shelters. These living conditions are worsened as reports surface of infections and infestations, as well as expired food being provided (Schuba & Malagón, 2023). One of these police stations is located near the West Side in the 12th district, where dozens of families sit outside with everything they own, some having left their country with only “the clothes on their backs.”(Perlman, 2023) Johon Torres, a Venezuelan who was moved to this station with his three daughters and niece details his current living conditions where, “every morning, they’re told to leave the station until 6 p.m. At night, they are allowed inside, sleeping along with other families in tight quarters. They haven’t taken a shower since they arrived at the station. Now, they wait for help from the city and for a bed of their own.” (Perlman, 2023) As resettling migrants out of police station lobbies became a priority, temporary city-run shelters opened throughout the city including Daley College on the South Side and Wilbur College on the Northwest Side. These shelters, however, were quickly running out of resources and struggling to meet demand. More recently, hundreds of migrants have been moved from these temporary shelters and police stations to the Northside lakefront neighborhoods. Local organizations, volunteers, and mutual aid groups have extended a helping hand to migrants by providing pop-up showers, clothing donations, hot meals, recreational activities, transportation, health screenings, and other temporary resources (Nuques, 2023). While conditions have slightly improved, persisting are concerns surrounding availability of housing and additional resources as migrants continue to arrive. Along with temporary housing services being provided to newly arrived migrants, children and teens are granted the opportunity to be enrolled in Chicago Public Schools. “Kids who just arrived today, yesterday and this week are registered for school and get all the supplies that they need to set them up and welcome them are here in Chicago,” said Kathleen Murphy, one of the volunteers from the mutual aid group, Todo Para Todos, that that helps migrant parents enroll their children (Medina & Ong, 2023). Twelve-year-old Yasmari Leon, a Venezuelan native who migrated with her father to Chicago and stayed at a temporary shelter, was able to finish out the last school year alongside other CPS children (Loria, 2023). Her father, Jackson Leon, expressed the importance of her enrollment when he said, “Here she can study again, learn English and learn another way of life.” (Loria, 2023) Ensuring that these students will have the resources to succeed academically will prove to be difficult as schools prepare to welcome new students “in the thousands” of which many require translation services and other basic services. Nonetheless, a CPS team lead by the district’s language and cultural education chief, Karime Asaf, are striving to efficiently direct resources to schools receiving these new students (Issa, Loria, & Moreno, 2023). Families who haven’t enrolled in school are located and directed to schools who are most likely to have the programs and space to support the student. Currently, there isn’t any clear long term plans that have been proposed to address this growing issue as efforts have solely focused on supplementing resources at the immediate moment. However, city officials need to administer long-term solutions and policies given that this issue will continue to persist if proper action is not taken. They should consider implementing a stable infrastructure for housing and long-term accessible resources (e.g., physical and emotional health, education, food access, clothing, and employment, among other resources) in communities as not only will it meet the needs of those that are just arriving but also for the overwhelming minority community in Chicago. Providing stability in these avenues for individuals and families is pivotal as it will provide a foundation by which they can begin to start their new life in this country. Resources Esperanza Health Centers Latinos Progresando Chicago Public Schools Food Distribution Center La Casa Norte References Hernandez, Acacia. “40 to 50 Migrants Arrive to Chicago by Bus Daily, Officials Say.” WTTW News, 4 Aug. 2023, https://news.wttw.com/2023/08/04/40-50-migrants-arrive-chicago-bus-daily-officials-say. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. Issa, Nader, et al. “CPS Juggles Funding, Bilingual Staff to Welcome Thousands of New Migrant Students.” Chicago Sun-Times, 20 Aug. 2023, https://chicago.suntimes.com/education/2023/8/20/23837103/cps-migrant-bilingual-students-public-schools. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. Loria, Michael. “Dozens of New Immigrants Joining Chicago Public Schools as School Year Nears End.” Chicago Sun-Times, 22 May 2023, https://chicago.suntimes.com/2023/5/22/23732754/migrants-chicago-public-schools-students-chldren-enrolled-lawndale-little-village. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. Medina, Andrea, and Eli Ong. “WGN-TV.” WGN-TV, 22 Aug. 2023, https://wgntv.com/news/chicago-news/chicago-non-profit-ctu-members-help-register-migrant-children-for-school/. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. Nuques, Katya. “Little Village Is a Model for How to Help Migrants in Chicago Build New Lives.” Chicago Sun-Times, 30 May 2023, https://chicago.suntimes.com/2023/5/30/23742465/migrants-chicago-little-village-community-organizing-katya-nuques-op-ed. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. Perlman, Marissa. “Chicago Police Station Houses Dozens of Migrant Families.” CBS Chicago, 9 May 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/chicago-police-station-migrants/. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. Schuba, Tom, and Elvia Malagón. “Immigrants Forced to Sleep on Floors, Eat Expired Meals at Shelters Run by Chicago Police.” Chicago Sun-Times, 1 May 2023, https://chicago.suntimes.com/2023/5/1/23707352/expired-food-infections-infestations-chicagos-police-stations-makeshift-shelters-migrants. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023. By Shaw Qin, AmeriCorps State & National Member In the past year, more than 8,000 migrants have arrived in Chicago seeking asylum and permanent residence (Bosman, 2023). Due to the city’s limited investment in resources and services for migrants, many are now staying in temporary shelters, police stations, and respite centers. At HOPES, we have also seen an increasing number of migrants in our programs, two of which now have 30% Spanish-speaking families. Amidst the public attention and debate, this migrant influx sheds light on an often invisible population and their experience – immigrants experiencing homelessness*.

* Unless otherwise specified, this article uses “immigrant” to refer to all types of immigrants, refugees, and international migrants, although the particular contexts of migration influence their housing experiences. Across the globe, international migration has continued to expand in recent years. As of 2020, migrants comprise 3.6% of the world population, compared to 2.8% two decades ago (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021). Among the countries migrants arrive in, the U.S. remains the primary destination, with over 51 million international migrants as of 2020. However, some of those migrants face precarious housing situations compounded by characteristics related to their immigrant status. According to a systematic review of immigrants’ housing experiences, immigrants’ barriers to stable and secure housing include interpersonal racism, past trauma and stress in their new environment, poor access to services (e.g., lack of awareness and language barriers), and limited financial resources (Kaur et al., 2021). Additionally, cultural backgrounds and differences may hinder immigrants from seeking housing services, such as immigrants not identifying as homeless (Couch, 2017) or cultural and religious incompatibility with housing service providers (Gilleland et al., 2016). Moreover, in the case of undocumented immigrants, their legal status strongly hinders their seeking services, due to their disqualifications in some public services and their fear of deportation if their status is revealed (Kaur et al., 2021). In summary, immigrants face various instabilities that could lead them to homelessness and barriers to services that could help them regain or maintain stability. The intersection of immigration and homelessness also poses unique challenges to educating children with this background. Students’ experiences of immigration, acculturation, and homelessness can lead to mental health issues and stress (Khan et al., 2022), which may affect their general well-being and educational outcomes (Rossen & Cowan, 2014). Furthermore, previously discussed barriers to service access can also increase the difficulty for children to benefit from educational services related to homelessness. Although students are eligible for services under the McKinney-Vento Act regardless of immigration and documentation status (SchoolHouse Connection, 2022), immigrant families may not know its existence or their eligibility (Sills-Carter, 2019). Relatedly, schools and other service providers may be unable to identify those immigrant students experiencing homelessness and provide multilingual services in a culturally sensitive manner (Sills-Carter, 2019). Moreover, many immigrant families experiencing homelessness live in housing situations called “doubling up,” or multiple families sharing living space (Gilleland et al., 2016, p. 16). Consequently, these families may not consider themselves homeless (Couch, 2017) and have housing situations similar to multigenerational households typical in many immigrants’ cultures (SchoolHouse Connection, 2022). This increases the difficulty of providing educational services for their children. Despite the barriers to housing stability, immigrants experiencing homelessness also display resilience in various ways, which should form the basis of serving this population. Multiple studies show that immigrants’ social capital (Im, 2016), including ethnic networks (Sills-Carter, 2019) and nurturing social and family connectedness (Khan et al., 2022), buffers the stress of housing insecurity. However, immigrants’ social and familial connections might not be enough to ensure housing stability unless the networks include ample knowledge or information on social support resources (Sills-Carter, 2019). In other cases, some immigrants do not have any social connections in this country. This is where service providers may come into the picture. Housing service providers can collaborate with the immigrant community and immigrant service providers to build cultural competence in serving the community. For educators, this can begin with collaboration among McKinney-Vento, Migrant Education, and English Language Learner programs in the school system and across community organizations with those specific focuses. This way, service providers can build on each others’ specialties. For example, programs on students’ homelessness may provide culturally-sensitive multilingual services after receiving training from the immigrant program, and immigrant programs may recognize students who could experience homelessness and make referrals. At HOPES, we strive to better meet the need of the migrant community by piloting a Spanish-only program and prioritizing recruiting bilingual site coordinators. Last but not least, service providers may encourage immigrants they serve to invite people in their social network to use their service if needed. In conclusion, educating immigrant students experiencing homelessness is crucial for their success. However, there is a dearth of research centering on this intersection, particularly in the U.S. educational setting, due to immigrant homelessness’s more invisible nature (e.g., “doubling up” and being unwilling or unable to receive service). Although research in other countries and on other topics (e.g., healthcare and immigrant homelessness) can inform educators’ work in the U.S., more research is critical in helping service providers understand the communities’ needs and develop best practices to ensure all students receive adequate education and services. Resources SchoolHouse Connection: Strategies for Supporting Immigrant and Migrant Students Experiencing Homelessness. National Center of Homeless Education: Translations of Homeless Education Materials References Bosman, J. (May 10, 2023). Open-armed Chicago feels the strains of a migrant influx. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/10/us/chicago-migrants-title-42.html Couch, J. (2017). “Neither here nor there”: Refugee young people and homelessness in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review, 74, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.014 Gilleland, J., Lurie, K, & Rankin, S. (2016). A broken dream: Homelessness & immigrants. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2776890 Im, H. (2011). A social ecology of stress and coping among homeless refugee families [Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota]. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. https://hdl.handle.net/11299/116170 Kaur, H., Saad, A., Magwood, O., Alkhateeb, Q., Mathew, C., Khalaf, G., & Pottie, K. (2021). Understanding the health and housing experiences of refugees and other migrant populations experiencing homelessness or vulnerable housing: A systematic review using GRADE-CERQual. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 9(2), E681-E692. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20200109 Khan, B. M., Waserman, J., & Patel, M. (2022). Perspectives of refugee youth experiencing homelessness: A qualitative study of factors impacting mental health and resilience. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 917200. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.917200 McAuliffe, M., & Triandafyllidou, A. (Eds.). (2021). World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022 Rossen, E., & Cowan, K. C. (2014). Improving mental health in schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(4), 8-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721714561438 SchoolHouse Connection. (June 16, 2022). Strategies for supporting immigrant and migrant students experiencing homelessness. https://schoolhouseconnection.org/strategies-for-supporting-immigrant-and-migrant-students-experiencing-homelessness/ Sills-Carter, A. (2019). Accessibility to resources for homeless documented immigrant families: A case study [Doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri - Saint Louis]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. What Goes Up, Keeps Going Up? The Damaging Effects of Wage Stagnation and Rent Hikes on Homelessness6/28/2023 When someone faces homelessness, there are often numerous hardships that have all contributed to the situation. Arguably chief among these hardships is lack of income due to stagnant wages or unemployment. Many Americans who live paycheck to paycheck are seeing that their wages are not keeping up with the continually rising cost of living in the United States. This problem is largely due to two concurrent damaging trends: government policies that have created stagnant wages and a general rise in rent and housing prices. In order to better understand how people can slip into homelessness, it's important to understand the myriad of causes behind stagnant wages and rising costs of living in the United States.

While the average wages of today fail to keep pace with the cost of living, this wasn’t always the case. Additionally - despite globalization and automation being blamed as primary causes for wage stagnation - there are many other factors at play that reveal a consistent history of corporate neglect for employees, lack of governmental intervention, and worries of stability among workers. One big way large corporations have contributed to stagnant wages is stock buybacks. A stock buyback is when a public company quite literally purchases its own stock from the open market, driving up the price of their stock which helps increase value for shareholders and executives at the company. This was considered market manipulation prior to 1982, when the SEC cut the regulation during Ronald Reagan’s presidency (AFR; Curry; Forbes). Since then, however, buybacks have become more common in recent years, even during the pandemic, increasing in “conjunction with rising executive compensation through stock-based pay packages” (AFR). According to Americans for Financial Reform, these buybacks “exacerbate the racial wealth gap, worsen economic inequality, and divert resources from the real economy which harms workers.” When corporations use their profits to create value for stockholders, the only people who lose are the workers themselves, as those profits could have been used to increase wages, improve benefits, and strengthen workplace safety and general infrastructure. A 2021 study by the American Compass found that “that the number of companies that extracted more value from their firms (including share buybacks) than they invested in new capital expenditures had risen from only 6 percent of companies before 1985 to 49 percent of companies in 2017” (AFR). This means that since the Reagan administration SEC cut the regulation that prohibited buybacks, multiple generations of millions of American workers have lost out on significant increases in pay, job security, and workplace safety because of corporate greed. Further, stock buybacks are inherently discriminatory because of the historic lack of equity within the stock market - while “white families hold 90 percent of the stock market value, [...] black and latinx households each own only 1 percent of the total stock market value — figures that have not budged for the past 30 years” (AFR). Looking at the government's role in this, we can see less and less intervention on behalf of the workers since the 1980’s. Between 1948 and 1970, worker productivity had a direct positive relationship with wages, so the more productive the American workforce was, the more benefits workers saw from their labor (EPI). This was due to specific policy that intentionally aimed to allow workers to directly benefit from their hard work. However, the late 1970’s and subsequent decades saw the stripping of these policies, forcing workers into very difficult positions. According to the Economic Policy Institute, “net productivity rose 61.8%, while the hourly pay of typical workers grew far slower—increasing only 17.5% over four decades” since 1979 (EPI). Due to these policy choices, the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour has less purchasing power today than it ever has in the last 66 years, and roughly two thirds of American wages have not kept pace with inflation and rising living costs (Cerulo CBS). Further, Scott Lincicome - Director of General Economics at Cato Institute - states that “in case after case, you see that government policies were implemented to discourage labor dynamism and to discourage workers from moving to a better job or moving to a better town or city to improve their job prospects” (Lee NBC). The immense disparity between pay increases and rising costs of living is one of the main causes of homelessness, as it is both incredibly difficult and stressful to find and pay for housing when your income has not increased with the cost of living. Much like wage stagnation, affordable housing availability has decreased despite worker productivity steadily increasing. Wage disparity coupled with increasingly less availability of affordable housing leaves many at extreme risk of becoming homeless (NAEH). And as the cost of affordable housing increases, a report from the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty states that 1 in 4 renters in the U.S. have “extremely low income” by the metrics of United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (Reddin LC). Further, 11 million households spend more than half of their income on rent, and 38 million households spend more than a third of their income on rent (NAEH 2). Since so much of their income is used to pay for housing, these households are just one medical emergency or unexpected bill from becoming homeless (NAEH 2). One important tool available to people in these situations is the Housing Choice Voucher (referred to as HVC from here on out) program, created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. However, HVCs are critically underfunded, and “increases in federal rental assistance have lagged far behind growth in the number of renters with very low incomes” (NAEH 2). And even though the HVC program is the largest rental assistance program in the country, only a fourth of eligible households actually receive help (NAEH). Unfortunately, economic policies that originated in the 1970’s and 1980’s have effectively made it very difficult for more than half of American households to live comfortably in an economy that prioritizes corporations and stockholders over workers. Despite the existence of government tools and programs to help people pay for housing, wages and other social safety nets continue to fall behind with the rising cost of living, which leaves millions of people living at severe risk of potential and/or certain homelessness every year. References Affordable Housing. (n.d.). National Alliance to End Homelessness. Retrieved June 26, 2023, from https://endhomelessness.org/ending-homelessness/policy/affordable-housing/ [email protected], G. R. (2019, September 29). Wage stagnation, lack of affordable housing greatest factors in homelessness. The Lawton Constitution. https://www.swoknews.com/special_reports/wage-stagnation-lack-of-affordable-housing-greatest-factors-in-homelessness/article_74e34411-f00a-5d73-ac15-49f134bf7723.html Income. (n.d.). National Alliance to End Homelessness. Retrieved June 26, 2023, from https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/what-causes-homelessness/incomeinequality/ Lee, J. (2022, July 19). Why American wages haven’t grown despite increases in productivity. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/07/19/heres-how-labor-dynamism-affects-wage-growth-in-america.html Most U.S. workers say their pay isn’t keeping up with inflation—CBS News. (2022, September 14). https://www.cbsnews.com/news/wages-not-keeping-up-with-inflation/ Team. (2021, November 10). Fact Sheet: Tax Corporate Stock Buybacks that Enrich Executives and Worsen Inequality. Americans for Financial Reform. https://ourfinancialsecurity.org/2021/11/fact-sheet-tax-corporate-stock-buybacks-that-enrich-executives-and-worsen-inequality/ The Productivity–Pay Gap. (n.d.). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved June 26, 2023, from https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/ What Is A Stock Buyback? – Forbes Advisor. (n.d.). Retrieved June 26, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/stock-buyback/ Resources National Alliance to End Homelessness | https://endhomelessness.org/ Economic Policy Institute | https://www.epi.org/ Americans for Financial Reform | https://ourfinancialsecurity.org/ By Jake Schwartz, AmeriCorps VISTA Program Coordinator The state of the healthcare system in the United States has long been the subject of intense debate - and oftentimes heavy criticism - for the perceived shortcomings of various aspects of healthcare that fail to adequately support patients. Among the most glaring issues within U.S. healthcare are the existing financial barriers for both primary care and emergency care, the variability of treatment outcomes across different socioeconomic levels, races, and genders, and the current lack of more accessible, non-traditional methods of receiving healthcare. While each of these facets can result in hardship for people from any walk of life, these negative effects are felt at a much greater intensity for those who face homelessness. When examining U.S. healthcare from a broad point of view, it becomes clear that these aforementioned issues - cost of care, treatment outcomes, lack of accessibility - serve to further the hardships of people who face homelessness.